Cinematography is the art and science of capturing moving images on film or digital media. It encompasses various techniques and tools to convey stories, emotions, and messages visually. Cinematographers use a combination of camera angles, movements, framing, and lighting to create compelling visuals that enhance storytelling. Each cinematography technique serves a specific purpose and can evoke different emotions or reactions from the audience.

Camera Techniques In Filmmaking:

1. Extreme Long Shot (ELS):

An extreme long shot (ELS) is a cinematic technique that captures a wide view of a location or setting, emphasizing the environment rather than specific details. This shot is often used to establish a scene’s context or showcase vast landscapes, setting the stage for the narrative to unfold.

One iconic example of the extreme long shot can be found in David Lean’s masterpiece, “Lawrence of Arabia.” In the film’s opening sequence, viewers are treated to breathtaking vistas of the desert landscape, as the camera pans across endless dunes and vast horizons. This shot not only immerses viewers in the protagonist’s journey but also emphasizes the epic scale of the desert terrain, setting the tone for the epic story that follows.

The extreme long shot can also be used to highlight the isolation or insignificance of characters within their surroundings. In “There Will Be Blood,” director Paul Thomas Anderson utilizes ELS to emphasize the desolation of the oil fields and the isolation of the protagonist, Daniel Plainview. As Plainview stands alone amidst the barren landscape, the vastness of the surroundings serves as a metaphor for his own inner emptiness and moral decay.

In summary, the extreme long shot is a powerful cinematic tool that allows filmmakers to establish context, convey scale, and evoke emotion through sweeping landscapes and expansive vistas. Whether used to showcase natural beauty, emphasize isolation, or set the stage for epic adventures, the extreme long shot adds depth and grandeur to the cinematic experience.

2. Bird’s Eye Shot:

A bird’s eye shot provides a top-down perspective, simulating the view from a bird in flight. This unique vantage point offers filmmakers the opportunity to reveal spatial relationships, patterns, and symbolism within a scene.

One notable example of the bird’s eye shot can be found in Stanley Kubrick’s “The Shining.” In the film’s climax, as Jack Torrance chases his son through the labyrinthine maze surrounding the Overlook Hotel, Kubrick employs a bird’s eye shot to capture the eerie beauty of the snow-covered maze. This shot not only emphasizes the characters’ isolation and vulnerability but also adds to the sense of disorientation and claustrophobia as they navigate the labyrinth.

The bird’s eye shot can also be used to convey themes of control and surveillance. In Alfred Hitchcock’s “Vertigo,” the director utilizes a bird’s eye shot during the iconic rooftop chase sequence to depict the protagonist’s fear and vulnerability as he becomes increasingly ensnared in the web of deception and manipulation.

In summary, the bird’s eye shot offers filmmakers a unique perspective from which to explore themes of isolation, control, and vulnerability. Whether used to highlight the maze-like complexities of the human psyche or to evoke a sense of awe and wonder at the beauty of the natural world, the bird’s eye shot adds depth and dimension to the cinematic experience.

3. Long Shot:

A long shot (LS) is a cinematic technique that frames the subject from a distance, showing their full body and surrounding context. This shot is often used to establish spatial relationships, emphasize characters’ actions within a larger setting, or convey a sense of scale and perspective.

One classic example of the long shot can be found in Peter Jackson’s “The Lord of the Rings” trilogy. In the epic battle sequences, Jackson utilizes long shots to convey the scale of the conflict and the vastness of the battlefield. As armies clash and warriors charge across expansive landscapes, the long shot captures the grandeur and spectacle of the epic struggle between good and evil.

The long shot can also be used to emphasize the characters’ isolation or vulnerability within their surroundings. In Sergio Leone’s “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly,” the director employs long shots to frame the iconic showdown between the film’s three protagonists against the backdrop of the desolate desert landscape. As the characters stand alone in the vast expanse, the long shot heightens the tension and anticipation leading up to the climactic confrontation.

In summary, the long shot is a versatile cinematic tool that allows filmmakers to establish context, convey scale, and evoke emotion through expansive landscapes and sweeping vistas. Whether used to showcase epic battles, emphasize characters’ isolation, or capture moments of dramatic tension, the long shot adds depth and spectacle to the cinematic experience.

4. Medium Shot:

A medium shot (MS) is a cinematic technique that frames the subject from the waist up, allowing viewers to observe their actions and expressions while still maintaining a sense of context and surroundings. This shot is often used during dialogue scenes or character interactions to foster intimacy and engagement with the audience.

One classic example of the medium shot can be found in Michael Curtiz’s “Casablanca.” Throughout the film, Curtiz utilizes medium shots to capture the emotional nuances of the characters’ interactions, particularly during key dialogue scenes between Rick and Ilsa. As the characters navigate the complexities of love, loyalty, and sacrifice, the medium shot allows viewers to connect with their emotions and motivations on a deeper level.

The medium shot can also be used to convey themes of vulnerability or intimacy. In Sofia Coppola’s “Lost in Translation,” the director utilizes medium shots to highlight the characters’ emotional isolation and longing for connection amidst the bustling streets of Tokyo. As Bob and Charlotte forge a bond amid the anonymity of a foreign city, the medium shot captures the intimacy and vulnerability of their fleeting connection.

In summary, the medium shot is a versatile cinematic tool that allows filmmakers to capture the subtleties of human emotion and interaction. Whether used to convey intimacy, vulnerability, or emotional depth, the medium shot adds richness and complexity to the cinematic experience, drawing viewers into the world of the characters and their relationships.

5. Close-Up Shot:

A close-up shot (CU) is a cinematic technique that zooms in on a specific detail or part of the subject, intensifying emotional impact or emphasizing significance. This shot is often used to capture subtle expressions, convey intimate moments, or draw attention to key plot points.

One iconic example of the close-up shot can be found in Alfred Hitchcock’s “Psycho.” During the infamous shower scene, Hitchcock utilizes close-up shots to intensify suspense and shock viewers with sudden violence. As the camera zooms in on Marion Crane’s face and the knife-wielding figure of Norman Bates, the close-up shot magnifies the tension and horror of the moment, leaving a lasting impression on audiences.

The close-up shot can also be used to convey intimacy or vulnerability. In Wong Kar-wai’s “In the Mood for Love,” the director employs close-up shots to capture the unspoken connection between the film’s two protagonists as they navigate the complexities of love and betrayal. As the camera lingers on their longing glances and hesitant gestures, the close-up shot invites viewers into the intimate world of their forbidden romance.

In summary, the close-up shot is a powerful cinematic tool that allows filmmakers to capture the raw emotion and intensity of the human experience. Whether used to evoke fear, suspense, intimacy, or vulnerability, the close-up shot adds depth and resonance to the cinematic experience, drawing viewers into the inner world of the characters and their emotions.

6. Extreme Close-Up Shot:

An extreme close-up shot (ECU) is a cinematic technique that magnifies a minute detail or feature, such as a character’s eyes or an object’s texture, intensifying audience focus and creating a sense of intimacy or tension. This shot is often used to convey emotions or highlight key elements within a scene.

One striking example of the extreme close-up shot can be found in Darren Aronofsky’s “Requiem for a Dream.” Throughout the film, Aronofsky utilizes extreme close-ups to depict the characters’ drug-induced experiences, immersing viewers in their disorienting reality. As the camera zooms in on dilated pupils, trembling hands, and sweating brows, the extreme close-up shot heightens the sense of paranoia and desperation, conveying the characters’ descent into addiction and despair.

The extreme close-up shot can also be used to convey intimacy or vulnerability. In Ingmar Bergman’s “Persona,” the director employs extreme close-ups to explore the fractured psyche of the film’s two protagonists as they confront their innermost fears and desires. As the camera lingers on their anguished expressions and fragmented identities, the extreme close-up shot blurs the boundaries between reality and illusion, inviting viewers into the complex world of the human mind.

In summary, the extreme close-up shot is a powerful cinematic tool that allows filmmakers to capture the subtle nuances of human emotion and experience. Whether used to convey tension, intimacy, or vulnerability, the extreme close-up shot adds depth and intensity to the cinematic experience, drawing viewers into the inner world of the characters and their struggles.

7. Dutch Angle Shot:

A Dutch angle shot tilts the camera to create a sense of disorientation or unease, conveying psychological tension or visual imbalance within a scene. This technique is often used to evoke feelings of instability, confusion, or foreboding.

One classic example of the Dutch angle shot can be found in Carol Reed’s “The Third Man.” Throughout the film, Reed utilizes Dutch angles to mirror the protagonist’s moral ambiguity and the chaotic post-war environment of Vienna. As the camera tilts to one side, framing the characters against skewed horizons and distorted architecture, the Dutch angle shot conveys the disorientation and moral uncertainty of the film’s central conflict.

The Dutch angle shot can also be used to convey psychological tension or emotional turmoil. In Christopher Nolan’s “Inception,” the director employs Dutch angles to disrupt the sense of reality within the dream world, adding to the film’s surreal atmosphere. As the camera tilts and spins to capture the characters’ shifting perceptions and fractured realities, the Dutch angle shot heightens the sense of disorientation and instability, blurring the lines between dream and reality.

In summary, the Dutch angle shot is a powerful cinematic technique that allows filmmakers to convey psychological tension, visual imbalance, and emotional turmoil within a scene. Whether used to evoke feelings of disorientation, confusion, or foreboding, the Dutch angle shot adds depth and complexity to the cinematic experience, drawing viewers into the inner world of the characters and their struggles.

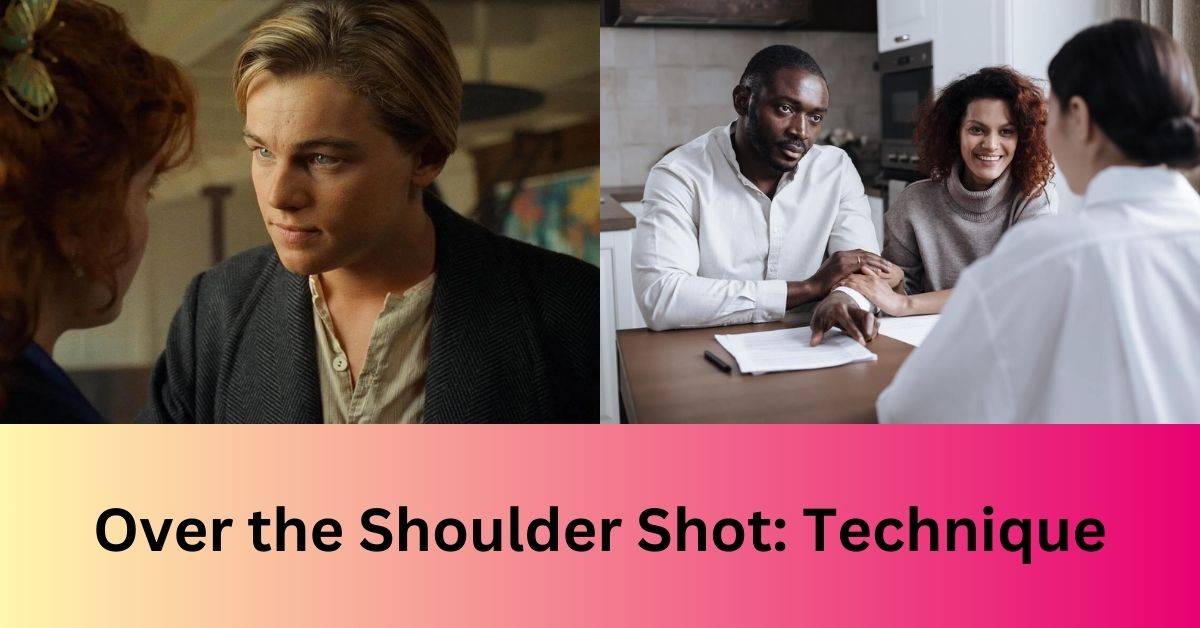

8. Over-the-Shoulder Shot:

An over-the-shoulder shot (OTS) positions the camera behind one character’s shoulder, framing their conversation partner in the foreground. This technique is often used during dialogue scenes or character interactions to establish spatial relationships, foster viewer engagement, and convey intimacy or tension.

One classic example of the over-the-shoulder shot can be found in David Fincher’s “The Social Network.” Throughout the film, Fincher utilizes over-the-shoulder shots to emphasize the characters’ dynamic exchanges and power struggles as they navigate the complexities of friendship, betrayal, and ambition. As the camera shifts between characters, framing their interactions from alternating perspectives, the over-the-shoulder shot draws viewers into the intimate world of their relationships, heightening the drama and tension of the narrative.

The over-the-shoulder shot can also be used to convey intimacy or vulnerability. In Richard Linklater’s “Before Sunrise,” the director employs over-the-shoulder shots to capture the intimate conversations and fleeting connections between the film’s two protagonists as they explore the streets of Vienna. As the camera lingers on their shared moments of laughter and introspection, the over-the-shoulder shot invites viewers into the intimate world of their burgeoning romance, heightening the emotional resonance of their encounter.

In summary, the over-the-shoulder shot is a versatile cinematic technique that allows filmmakers to establish spatial relationships, foster viewer engagement, and convey intimacy or tension within a scene. Whether used to capture dynamic exchanges between characters or evoke feelings of vulnerability and connection, the over-the-shoulder shot adds depth and complexity to the cinematic experience, drawing viewers into the inner world of the characters and their relationships.

9. Tilt Shot:

A tilt shot involves angling the camera vertically, either upward or downward, to reveal the subject or setting from a different perspective. This technique can create a sense of awe or vulnerability, depending on the direction of the tilt, and can be used to convey themes of power, perspective, and emotion.

One classic example of the tilt shot can be found in Orson Welles’ “Citizen Kane.” In the film’s opening sequence, Welles utilizes a dramatic tilt shot to reveal the imposing façade of Kane’s mansion, Xanadu, towering over the landscape. As the camera tilts upward, framing the mansion against the sky, the tilt shot conveys the grandeur and ambition of Kane’s empire, setting the stage for the epic tale of wealth, power, and corruption that follows.

The tilt shot can also be used to convey vulnerability or disorientation. In Roman Polanski’s “Rosemary’s Baby,” the director employs a downward tilt shot during the film’s climactic revelation to convey the protagonist’s sense of helplessness and dread. As the camera tilts downward, framing Rosemary against the oppressive ceiling of her apartment, the tilt shot heightens the tension and claustrophobia of the scene, emphasizing her isolation and vulnerability in the face of supernatural forces.

In summary, the tilt shot is a powerful cinematic technique that allows filmmakers to convey themes of power, perspective, and emotion through subtle changes in camera angle. Whether used to capture the grandeur of an imposing mansion or the vulnerability of a frightened protagonist, the tilt shot adds depth and dimension to the cinematic experience, drawing viewers into the inner world of the characters and their struggles.

10. Panning Shot:

A panning shot involves moving the camera horizontally from one side to another, following a subject’s movement, or scanning a scene. This technique provides a dynamic perspective and captures fluid motion within the frame, allowing filmmakers to convey a sense of movement, momentum, and continuity.

One classic example of the panning shot can be found in Lana and Lilly Wachowski’s “The Matrix.” Throughout the film’s iconic action sequences, the Wachowskis utilize panning shots to track the characters’ movements and choreography, immersing viewers in the frenetic pace of the fight scenes. As the camera pans from one character to another, following the action with fluid precision, the panning shot enhances the sense of excitement and intensity, drawing viewers into the heart of the action.

The panning shot can also be used to convey a sense of scale or perspective. In Steven Spielberg’s “Jurassic Park,” the director employs a sweeping panning shot to reveal the awe-inspiring majesty of the film’s titular dinosaurs. As the camera pans across the lush landscape of Isla Nublar, framing the towering brachiosaurus against the backdrop of the jungle, the panning shot conveys the grandeur and spectacle of the prehistoric world, inspiring a sense of wonder and awe in viewers.

In summary, the panning shot is a versatile cinematic technique that allows filmmakers to convey movement, momentum, and continuity within a scene. Whether used to track the action of a thrilling fight sequence or capture the majesty of a prehistoric landscape, the panning shot adds dynamism and excitement to the cinematic experience, drawing viewers into the immersive world of the film.

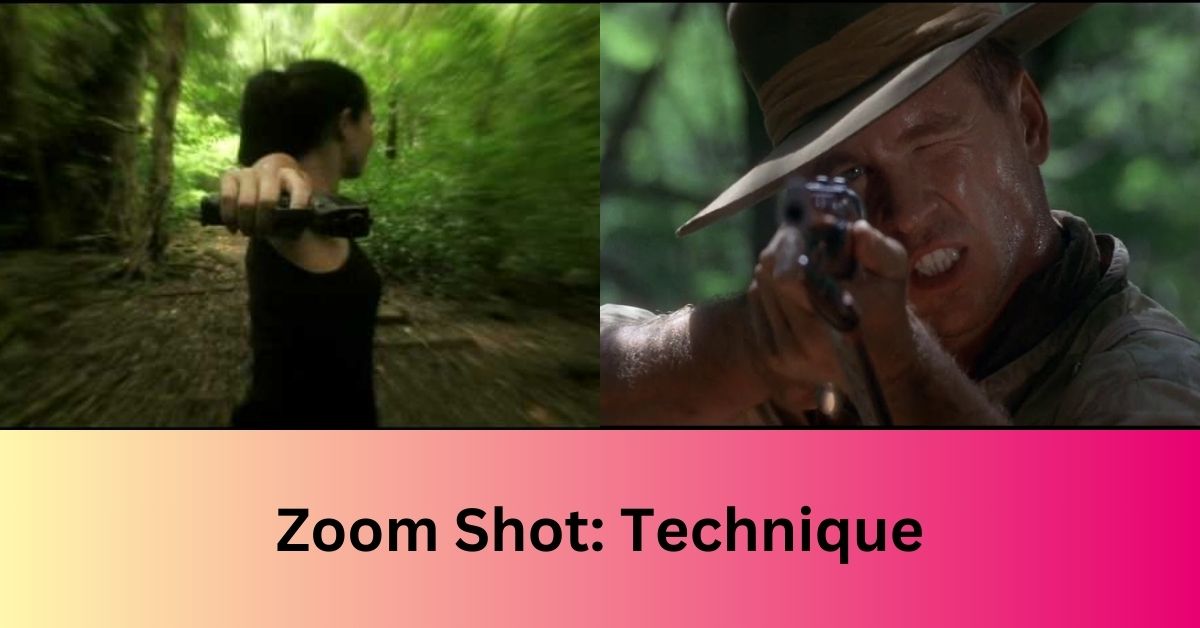

11. Zoom Shot:

A zoom shot involves adjusting the focal length of the lens to magnify or reduce the subject within the frame, creating a sense of intimacy or distance. This technique is often used to draw attention to specific details, convey dramatic effect, or establish spatial relationships within a scene.

One classic example of the zoom shot can be found in Steven Spielberg’s “Jaws.” Throughout the film, Spielberg utilizes zoom shots to intensify the suspense during shark attacks, gradually revealing the danger lurking beneath the surface. As the camera zooms in on the terrified faces of the characters and the menacing silhouette of the shark, the zoom shot magnifies the tension and horror of the moment, heightening the audience’s sense of anticipation and fear.

The zoom shot can also be used to convey emotional impact or significance. In Francis Ford Coppola’s “The Godfather,” the director employs a slow zoom shot during the film’s iconic baptism sequence to underscore the weight of Michael Corleone’s decision to assume control of the family empire. As the camera slowly zooms in on Michael’s face, framing his solemn expression against the backdrop of the church, the zoom shot emphasizes the gravity of his actions and the moral consequences of his choices.

In summary, the zoom shot is a powerful cinematic technique that allows filmmakers to manipulate perspective, convey emotion, and control the viewer’s focus within a scene. Whether used to heighten suspense during a tense confrontation or underscore the emotional weight of a pivotal moment, the zoom shot adds depth and intensity to the cinematic experience, drawing viewers into the inner world of the characters and their struggles.

12. Crane Shot:

A crane shot involves mounting the camera on a crane or boom arm to achieve high-angle or aerial perspectives, providing sweeping views and fluid movements within a scene. This technique is often used to convey grandeur, spectacle, and visual storytelling, allowing filmmakers to capture dynamic perspectives and immersive environments.

One classic example of the crane shot can be found in Martin Scorsese’s “Goodfellas.” Throughout the film, Scorsese utilizes crane shots to navigate through crowded spaces and convey the characters’ rise and fall within the criminal underworld. As the camera swoops and glides through the bustling nightclub, framing the characters against the backdrop of swirling lights and pulsating music, the crane shot immerses viewers in the vibrant atmosphere of the era, capturing the energy and excitement of the criminal lifestyle.

The crane shot can also be used to convey a sense of awe or spectacle. In Ridley Scott’s “Blade Runner,” the director employs a sweeping crane shot to introduce viewers to the dystopian world of Los Angeles, in 2019. As the camera ascends above the city streets, framing the sprawling metropolis against the backdrop of neon-lit skyscrapers and billowing smokestacks, the crane shot conveys the scale and complexity of the futuristic landscape, setting the stage for the film’s noir-inspired narrative.

In summary, the crane shot is a versatile cinematic technique that allows filmmakers to capture grandeur, spectacle, and visual storytelling within a scene. Whether used to navigate through crowded spaces or convey the scale of a futuristic metropolis, the crane shot adds depth and immersion to the cinematic experience, drawing viewers into the immersive world of the film.

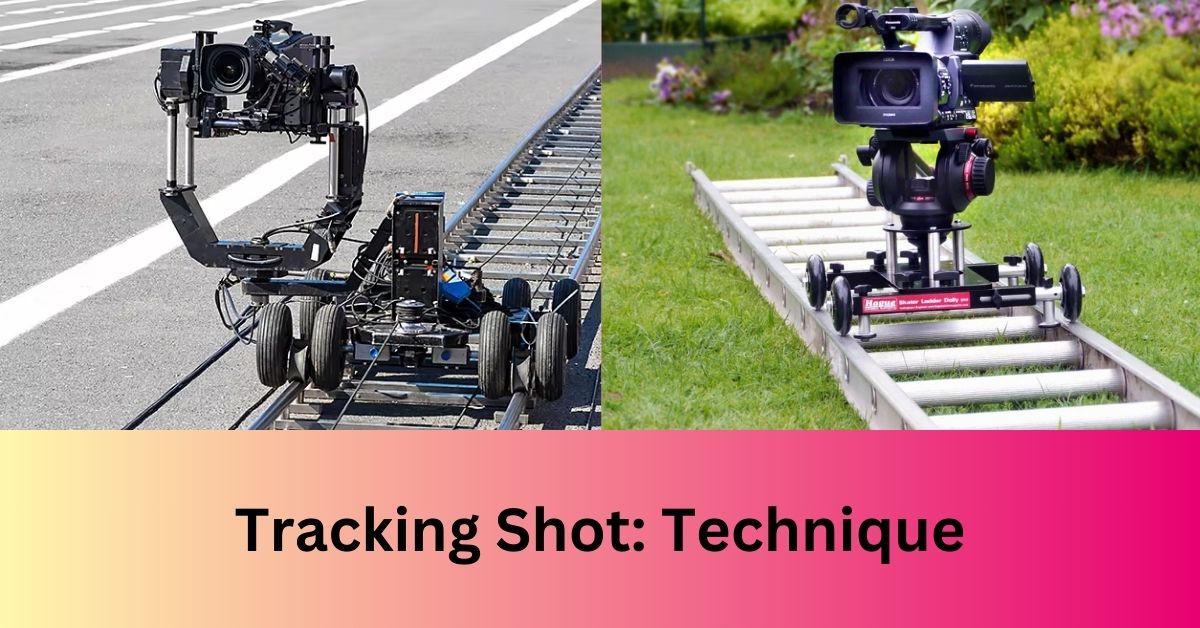

13. Tracking Shot:

A tracking shot involves moving the camera alongside or parallel to a moving subject, maintaining consistent framing and perspective. This technique creates a sense of momentum, immersion, and continuity within a scene, allowing filmmakers to capture dynamic perspectives and fluid motion.

One classic example of the tracking shot can be found in Alfonso Cuarón’s “Children of Men.” Throughout the film, Cuarón utilizes long tracking shots to immerse viewers in the dystopian world of a near-future society on the brink of collapse. As the camera follows the characters through chaotic city streets and war-torn landscapes, maintaining a seamless perspective and fluid motion, the tracking shot enhances the sense of urgency and immersion, drawing viewers into the heart of the action.

The tracking shot can also be used to convey a sense of intimacy or vulnerability. In Paul Thomas Anderson’s “Boogie Nights,” the director employs a fluid tracking shot to introduce viewers to the film’s sprawling ensemble cast, weaving through the crowded corridors of a nightclub and capturing the kinetic energy and excitement of the disco era. As the camera glides effortlessly from one character to another, maintaining a seamless perspective and fluid motion, the tracking shot immerses viewers in the vibrant world of the film, setting the stage for the epic tale of ambition, desire, and downfall that follows.

In summary, the tracking shot is a powerful cinematic technique that allows filmmakers to capture momentum, immersion, and continuity within a scene. Whether used to navigate through crowded spaces or convey the intimacy of a character’s emotional journey, the tracking shot adds depth and dynamism to the cinematic experience, drawing viewers into the immersive world of the film.

14. Point-of-View Shot:

A point-of-view shot (POV) adopts the perspective of a character, offering glimpses of their subjective experience and allowing viewers to see the world through their eyes. This technique fosters empathy, immersion, and engagement, allowing filmmakers to convey emotions, thoughts, and perceptions through visual storytelling.

One classic example of the point-of-view shot can be found in Robert Montgomery’s “Lady in the Lake.” In this innovative film noir, Montgomery utilizes a first-person POV shot to immerse viewers in the detective’s investigation, blurring the lines between reality and perception. As the camera adopts the detective’s perspective, framing the action from his point of view, the POV shot invites viewers into the immersive world of the film, allowing them to experience the mystery and intrigue firsthand.

The point-of-view shot can also be used to convey a character’s emotional state or psychological perspective. In Darren Aronofsky’s “Black Swan,” the director employs a subjective POV shot to convey the protagonist’s descent into madness and obsession. As the camera adopts Nina’s perspective, framing the action from her point of view, the POV shot heightens the sense of claustrophobia and paranoia, drawing viewers into the dark and twisted world of her psyche.

In summary, the point-of-view shot is a powerful cinematic technique that allows filmmakers to convey empathy, immersion, and engagement through visual storytelling. Whether used to immerse viewers in the subjective experience of a character or convey the emotional intensity of a psychological thriller, the POV shot adds depth and dimension to the cinematic experience, drawing viewers into the inner world of the characters and their struggles.

Conclusion:

Mastering cinematography techniques is essential for filmmakers to effectively convey their vision and engage audiences on a visual and emotional level. From extreme long shots to point-of-view shots, each technique offers unique opportunities for storytelling and expression. By understanding the uses, effects, and intricacies of different shot types, directors can elevate their craft and create compelling cinematic experiences that resonate with viewers long after the credits roll. Whether capturing sweeping landscapes, intimate moments, or heart-pounding action, cinematography techniques are the cornerstone of visual storytelling in film.

In conclusion, cinematography techniques are the backbone of visual storytelling in cinema, allowing filmmakers to convey emotions, evoke empathy, and immerse audiences in the world of the film. By mastering various shot types, directors can harness the power of visual language to communicate their vision and captivate viewers. From extreme long shots to point-of-view shots, each technique offers unique opportunities for creativity and expression, enriching the cinematic experience for audiences around the world.

Must Read: How to Become a Filmmaker? Unlock Your Filmmaking Dreams Today!